In light of the devastation of the 2020 bushfires, the investigation explores crisis response in regional NSW within the framework of architecture theory and urban planning. Various studies has noted that current fire measures could be improved significantly if the community and unique place-identity is taken into consideration; resulting in a tailored crisis response for each town. The place-identity and attachment is formed by locals through everyday vernacular interactions, enabling them with the first-hand knowledge and strength to overcome crises. This connection is sacred, hard to comprehend by outsiders and policy makers; as such, the involvement of the community in legislation is crucial. The essay elaborates on these suggestions, bringing in an example of community engagement in urban planning in the aftermath of the Christchurch Earthquake 2011.

WORK SCOPE

Community Research, Essay Writing, Editorial Formatting and Layout with InDesign, Infographics, Illustrations, Editing of Images, Mapping

Preliminary Site Study

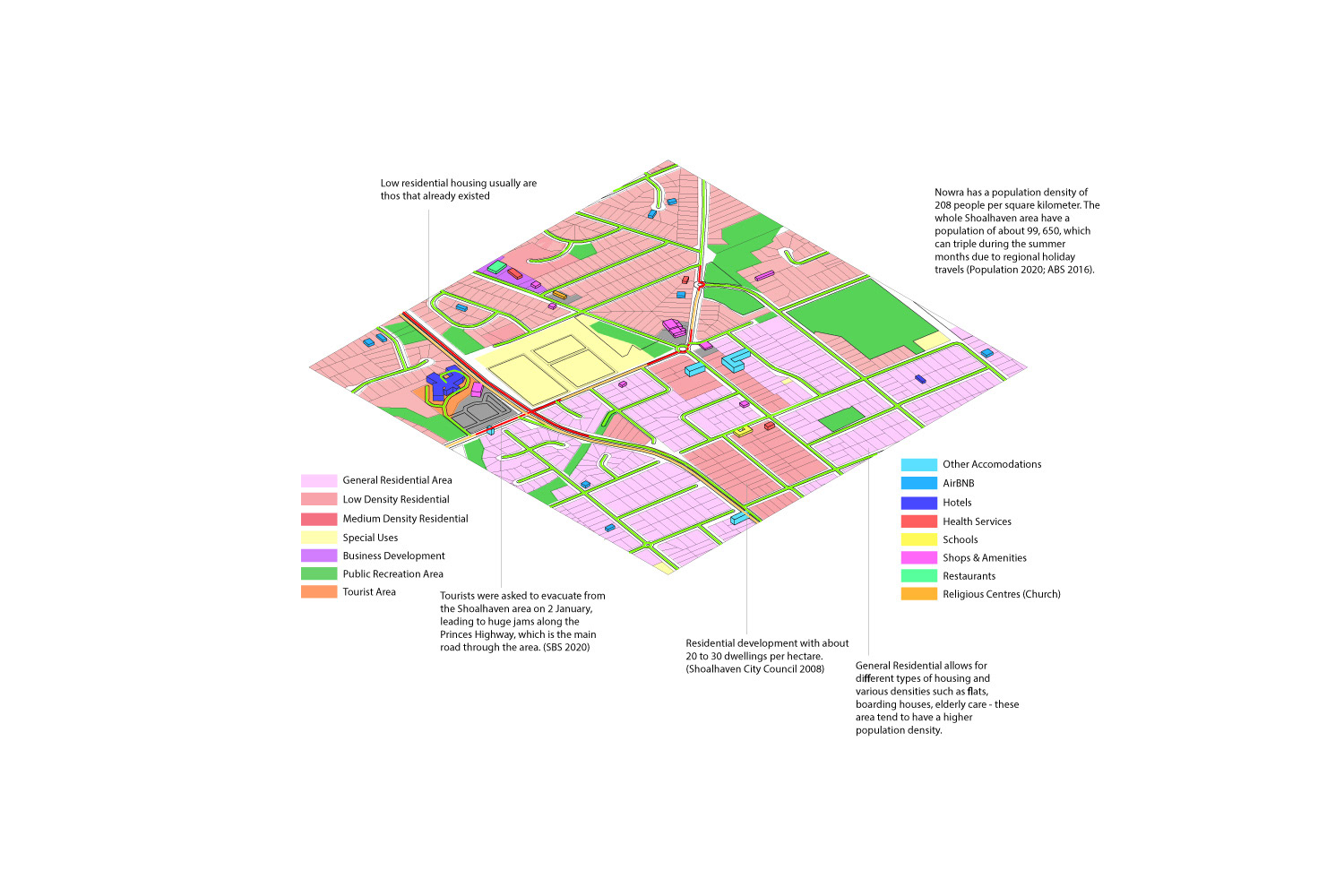

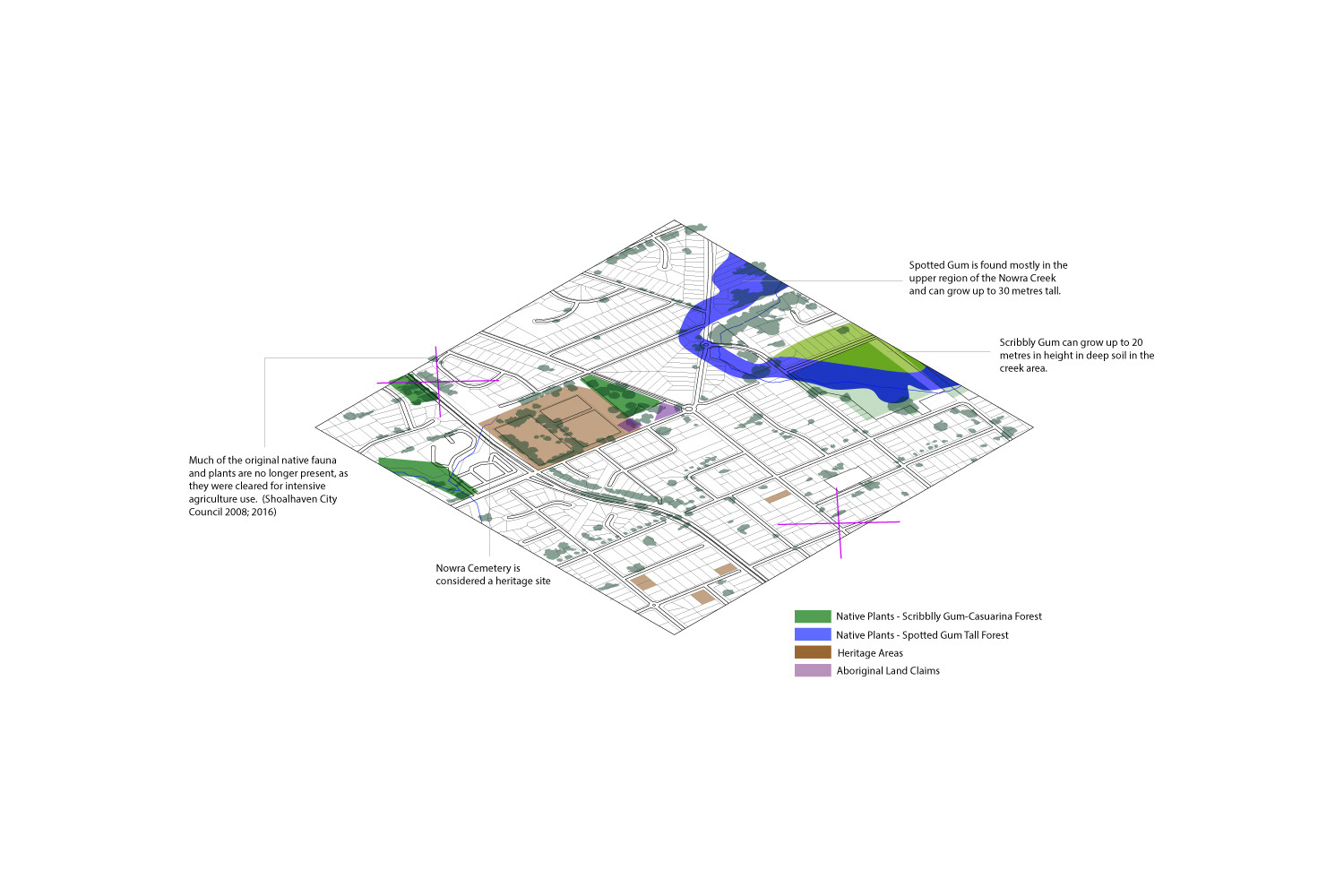

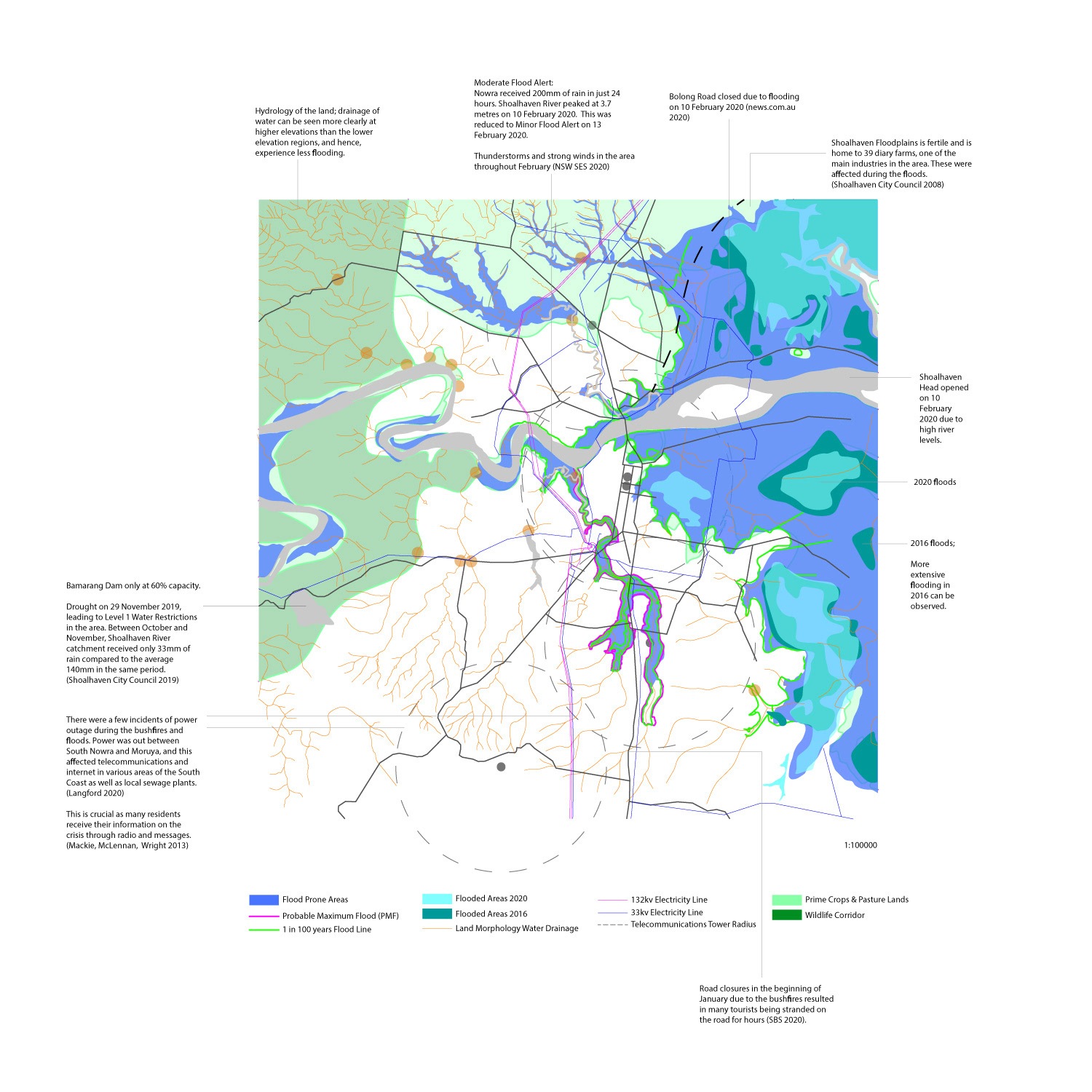

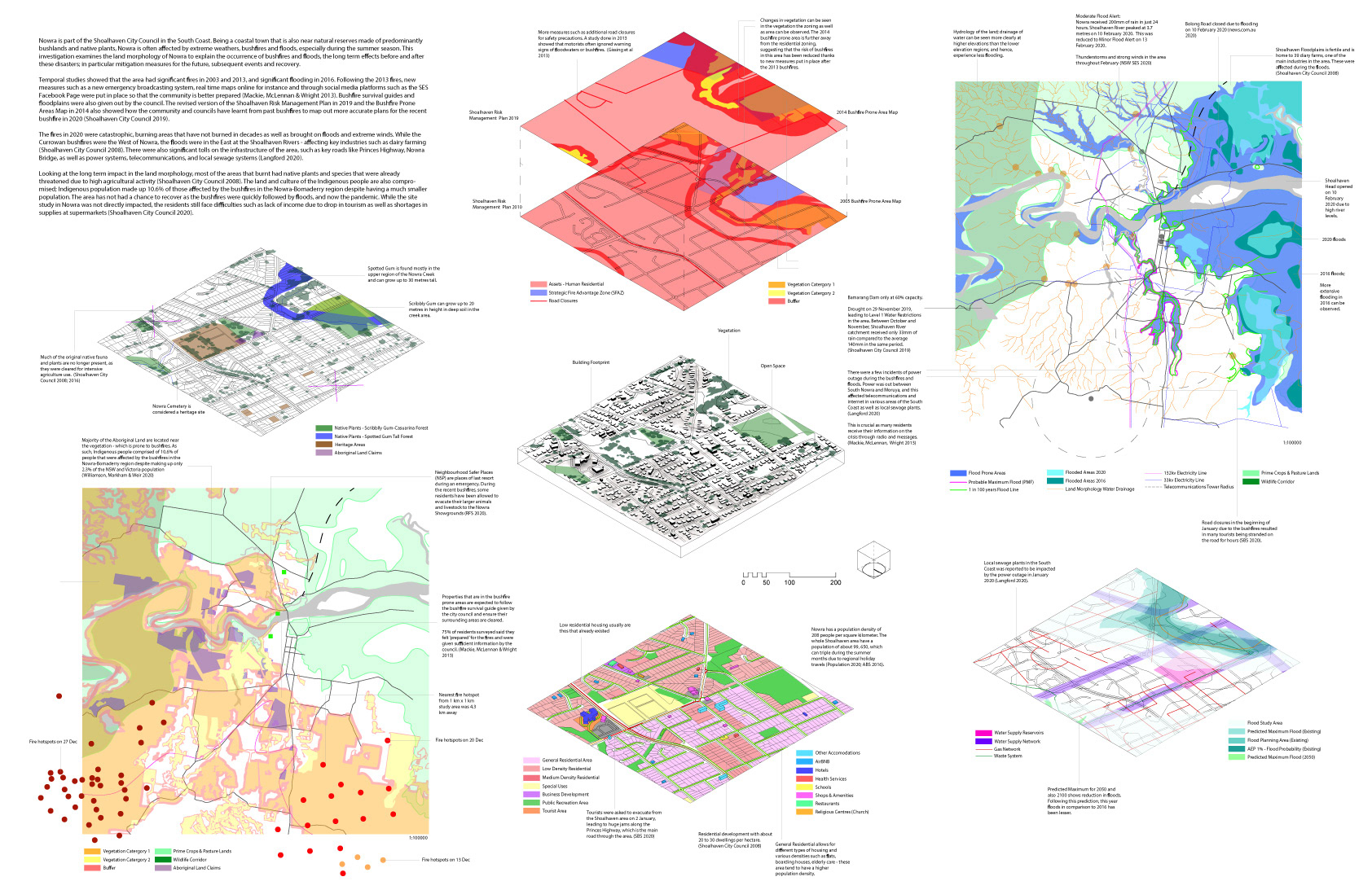

Nowra is part of the Shoalhaven City Council in the South Coast. Being a coastal town that is also near natural reserves made of predominantly bushlands and native plants, Nowra is often affected by extreme weathers, bushfires and floods, especially during the summer season. This investigation examines the land morphology of Nowra to explain the occurrence of bushfires and floods, the long term effects before and after these disasters; in particular mitigation measures for the future, subsequent events and recovery.

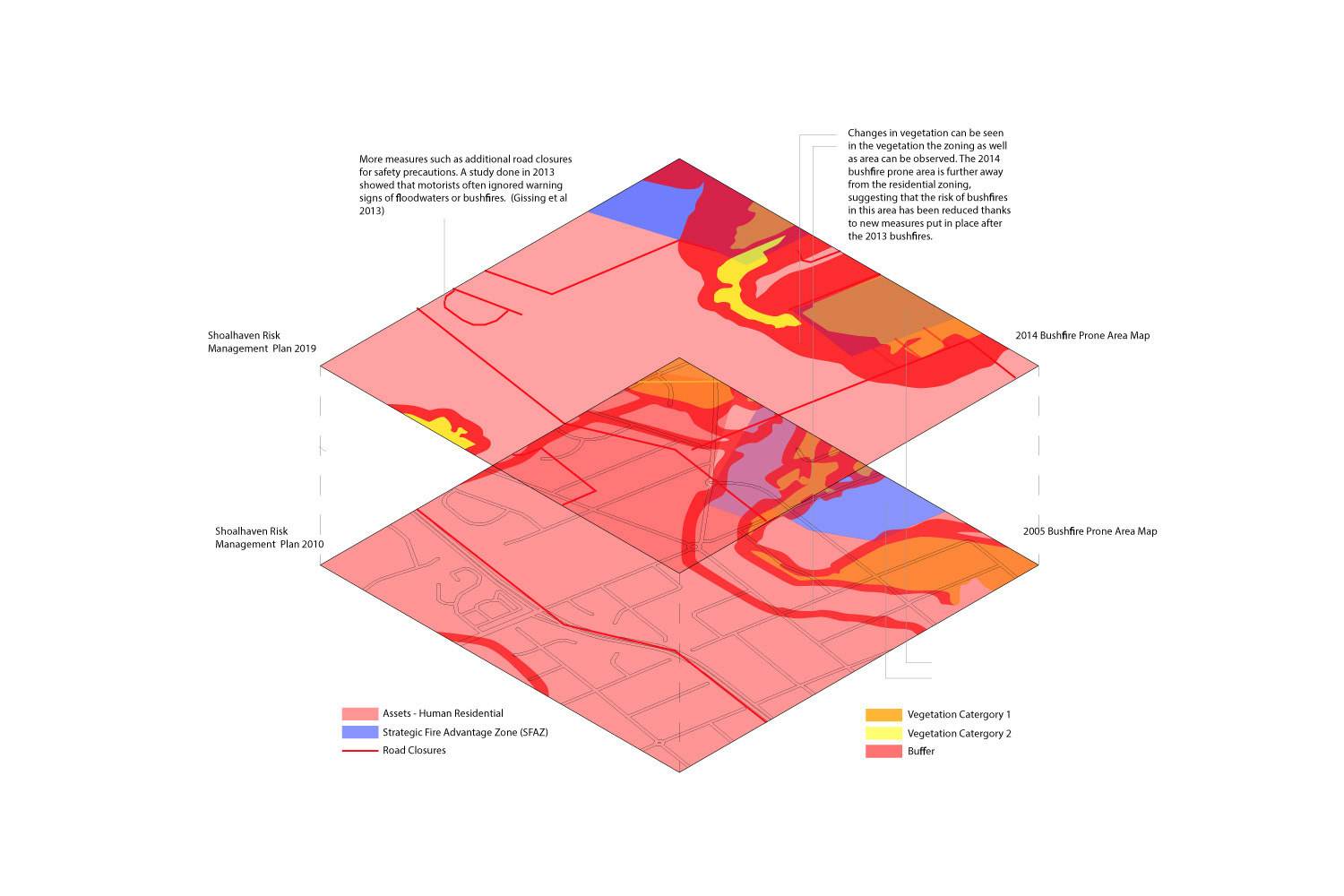

Temporal studies showed that the area had significant fires in 2003 and 2013, and significant flooding in 2016. Following the 2013 fires, new measures such as a new emergency broadcasting system, real time maps online for instance and through social media platforms such as the SES Facebook Page were put in place so that the community is better prepared (Mackie, McLennan & Wright 2013). Bushfire survival guides and floodplains were also given out by the council. The revised version of the Shoalhaven Risk Management Plan in 2019 and the Bushfire Prone Areas Map in 2014 also showed how the community and councils have learnt from past bushfires to map out more accurate plans for the recent bushfire in 2020 (Shoalhaven City Council 2019).

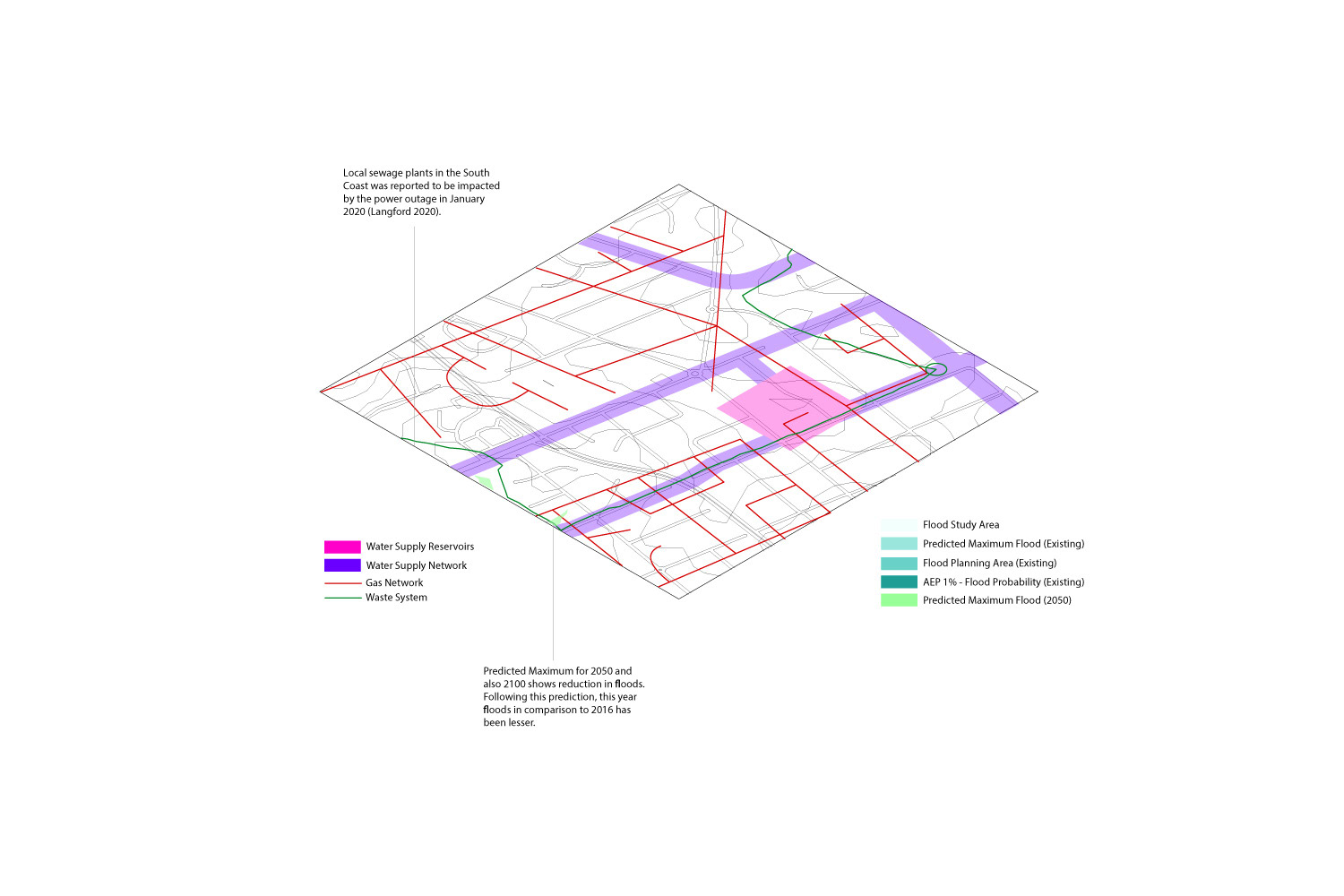

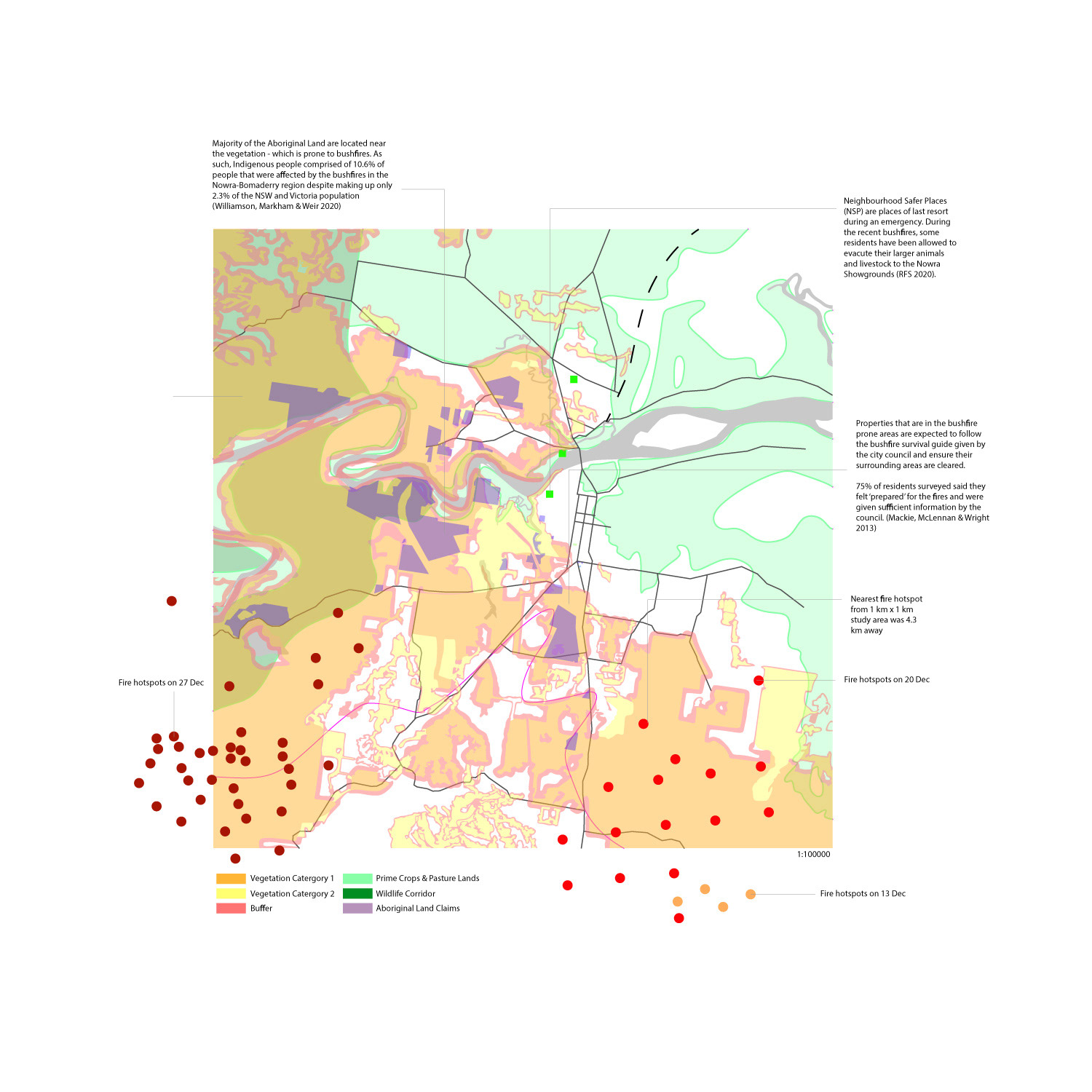

The fires in 2020 were catastrophic, burning areas that have not burned in decades as well as brought on floods and extreme winds. While the Currowan bushfires were the West of Nowra, the floods were in the East at the Shoalhaven Rivers - affecting key industries such as dairy farming (Shoalhaven City Council 2008). There were also significant tolls on the infrastructure of the area, such as key roads like Princes Highway, Nowra Bridge, as well as power systems, telecommunications, and local sewage systems (Langford 2020).

Looking at the long term impact in the land morphology, most of the areas that burnt had native plants and species that were already threatened due to high agricultural activity (Shoalhaven City Council 2008). The land and culture of the Indigenous people are also compromised; Indigenous population made up 10.6% of those affected by the bushfires in the Nowra-Bomaderry region despite having a much smaller population. The area has not had a chance to recover as the bushfires were quickly followed by floods, and now the pandemic. While the site study in Nowra was not directly impacted, the residents still face difficulties such as lack of income due to drop in tourism as well as shortages in supplies at supermarkets (Shoalhaven City Council 2020).

Nowra, NSW 2541

Place-Identity and Community Engagement

in Urban Planning for Resilient Crisis Response

Climate change is set to be an ever pressing issue that can lead to extreme crises; such as the unprecedented Australian bushfires in 2020.[1] In its destructive wake, it has ignited a conversation on how urban ecologies should adapt through spatial planning for sustainable and resilient communities. Estimates indicated that 68% of the world’s population will live in urban areas by 2050;[2] the high population densities, increase in vulnerable populations and dependence on networked infrastructure meant cities are progressively vulnerable to climate change.[3] With urban ecologies slowly but steadily waking up to the significance of community engagement in urban planning for crises, this article investigates building crisis resilient and sustainable communities through case studies of Nowra, New South Wales (NSW), Australia and Christchurch, New Zealand.

Shared responsibility and community-led initiatives are regarded as holy grails for resilient communities by policy makers such as the Australia’s National Strategy for Disaster Resilience (NSDR).[4] Whilst great in theory, the lack of proper coordination between government agencies and the locals directly impacted by crises has resulted in mismatched expectations and actions.[5] There is a power hierarchy of passive government experts implementing policies from a distance that overlooks the individual and collective experience of crises which should inform their responses similarly explored by Kosela.[6] This infringes on the public’s “right to the city”,emphasising an imbalance between people and governance regarding the development of the urban morphology.[7] Consequently, community engagement is often thwarted by the fantasy of the “imagined community” built upon the myth that a community is a fixed entity honing a self-absorbed narrow perspective.[8,9]

“Often communities are quite fractured [before a disaster] but you don’t notice it because people just get on separately doing their own thing.”[9]

Various studies have indicated affected communities do not respond to the NSW government Fire Danger Ratings (FDR) warnings as intended. The Australian fire warning system utilises multiple media platforms and permits residents to choose to evacuate or stay and defend.[10] Whilst locals found the warnings easy to understand, generally low risk perception and tendency to wait for absolute confirmation of a fire to avoid unnecessary costs resulted in lower fire preparedness levels than the governing power’s ideals.[11] Additionally, official bushfire survival plans and activities are targeted at individual households rather than strengthening the community; even though a stronger sense of community has been proven to boost inclination to endorsed preparation activities.[12] Conversely, should these recommendations differ from local knowledge, members of the community can be influenced to oppose them, reinforcing the imperative role of the community in crisis response.[13]

EXPLORATION OF THE URBAN IMAGINARY AND PLACE IDENTITY IN NOWRA

The commercial centre of the popular regional tourism Shoalhaven City, Nowra is a complex interplay between urban and rural.[14] Located 160km south of Sydney and lining the urban bush interface and coastal land, Nowra can be defined as peri-urban.[15] Sandwiched between fire prone bush lands in the West and low lying flood plains in the East, extreme weather and the threat of droughts, floods and bushfires constantly loom upon its 30,853 residents.[16] Since late 2019, Nowra has been struck by an onslaught of continuous crises; first the drought in November, then the Currowan bushfire in December, flooding at key diary industries in February and currently the COVID-19 pandemic.[17]

Despite paramount risk to natural crises, majority are long-term residents who have a strong connection to the surrounding landscape.[18] Thriving from previous bushfires in 2003 and 2013, the community is tough and experienced.[19] More than just a “summer tourism spot”, the “place-identity” comprises vernacular memory through everyday interactions with the urban morphology that informs local environmental knowledge, experience and attachment to the ecology.[20] As such, local perception of Nowra can differ from the wider public and governmental perception (Figure 1).

Figure 1. The interplay between the Insider and the Outsider Perspectives, and how that affects the Place-Identity and perception of the 2020 Bushfire crisis.

Even with conflicting viewpoints, it can be argued that Nowra has a distinctive identity that has to be factored into risk management strategies. Another aspect to consider is the difference in crisis as portrayed to the wider public through media and the actual “urban imaginary” shaped by the collective consciousness of the locals (Figure 1).[21] From community Facebook groups, charity drives to bushfire relief meetings, community-led recovery is starting to take form in Nowra; a privatised facet. An agglomeration of identity moulded by the community transforming into urban resilience.

Figure 2. Comparison of Nowra and Christchurch Urban Morphology

In reaction to population growth, the urban sprawl invaded further into the bush lands, heightening the bushfire risk.[22, 23] Whilst the majority of the population live in the more urbanised centre, a significant number in West Nowra and Nowra Hill in the south are far more exposed to bushfire risk (Figure 2). Notably, the Aboriginal population accounts for 10.6% of affected residents despite only being 8.8% of the overall Nowra population; highlighting inequalities in crisis vulnerability.[24] Multiple studies have indicated age, financial situation and location as factors for vulnerability.[25] In the context of Nowra, it can be argued that urban planning and accessibility to resources are imperative to mitigating vulnerability inequality.

In the vein of Koolhaas’ ‘The Generic City’, the urban morphology of Nowra follows the bias centre and lax periphery.[26] Being surrounded by hazard prone lands, a forced centralization of key amenities and residential developments hinder accessibility and intensify vulnerability. With only the Princes Highway as the main circulation throughout the town, its vulnerability to fire disaster and congestion separating those along the periphery from the centralised services and necessities. This problem is again repeated in the COVID-19 lockdown, perpetuated in the disparity in access to already minimal resources.[27] With such significant differences in vulnerability to the crisis, the cohesive experience of the “imagined community” is a far-fetched idealisation.

Koolhaas also argued that this dependency on the centre holds the ecology back from expansion and renewal from crisis, and suggested a break from the captivity of the identity for logical crisis response.[28] However, with more discussions on place-identity is a way to build community resilience, is it worth comprising one for another? It can be argued that identity is tightly woven into the fabric of society that it lives in and continually shapes urban morphology. Is there a way to still cultivate the identity and progress towards adaptive planning for crisis resilience?

THE BEST OF BOTH WORLDS? A LOOK AT THE COMMUNITY-LED APPROACH TO URBAN PLANNING FOLLOWING THE 2011 CHRISTCHURCH EARTHQUAKE

Resilience no longer just means to “bounce back”, but to anticipate and be proactive in planning for a sustainable community.[30] Rising from the rubble, Christchurch is hailed as a trailblazer in community engagement to aid spatial planning in the aftermath of the devastating Darfield earthquake of 2010 followed by the Christchurch Earthquake of 2011. The epicentre was 10km from the Central Business District (CBD), claiming lives and devastating infrastructures in the main city and unveiled opportunities for renewal of the urban morphology.[31]

“Christchurch would never be the same again, it will be better.”[29]

Community engagement played a central role in the recovery. Through social media, the community provided support, resources and assistance in cleaning up.[32] Cross collaboration between the Christchurch City Council and community was established through the ‘Share an Idea’ initiative, in which locals exchanged over 106,000 ideas of how the city should be rebuilt (Figure 3) utilising social media platforms, surveys, expos and workshops. The Draft Central City Plan was conceived, engaged in community feedback through the ‘Tell Us What you Think’ process.[33] By ensuring that the plan truly reflected the locals’ hopes and visions, strengthening the “place-identity”.

Figure 3. People of Christchurch coming together to share their vision for the future

“There is an enormous sense of ownership and commitment to rebuild Christchurch as a strong city for the 21st century...”[34]

The new Central City Plan implemented changes to zoning, building heights and density, accessibility and introduced green spaces and celebration of Christchurch’s heritage (Figure 4). Despite the more compact CBD to cultivate the heritage and businesses in the area, key amenities are still widely spread out across greater Christchurch, combined with the new transport network and cycling tracks.[35] This meant accessibility to resources are not compromised. Koolhaas’ idea of decentralisation for adaptability aligns, but at the same time, challenges his idea of breaking the core identity.

Figure 4. Some of the initiatives from the Christchurch Central City Plan after the 2011 Earthquake

Christchurch has a population of 398,520, and is considerably more developed than Nowra.[36] Liquefaction and rocks affected numerous residential areas, displacing locals and leading to new rezoning (Figure 2). As such, it can be observed that the population do not reproach into hazard prone areas, a stance against the urban sprawl along the periphery seen prior to the earthquakes (Figure 2).[37] The introduction of red zoning and the removal of housing estates in those areas are sustainable approaches to minimise future risks. Meanwhile, technical categories inform respective adaptive measures, such as urban design. controls and well-designed low rise buildings, for more resilient urban morphology as a proactive approach to future crisis.[38]

The lowered risk to hazards by mitigation of urban sprawl and equal accessibility to resources indicate lower vulnerability in the face of future crises; a catalyst for higher resilience.[39] Combined with the strong place-identity fostered through direct involvement and ownership to the urban morphology, the Christchurch community holds strong.

However, it has to be acknowledged that while Christchurch is hailed as a success story of community engagement in crisis, it is not a cookie-cutter approach for all. Additionally, it has to be noted that the article is observing these case studies from an outsider perspective and does not seek to provide a recommendation; but rather add to the ongoing discussion. Locality of the urban morphology, unique landscapes and individual stories of the community must be accounted for to cultivate resilient communities.[40] Decentralisation and increased significance of the periphery for adaptability do not need to come at the expense of place-identity. Further examination of vulnerability is required to strengthen resilience. The various stakeholders involved in crisis management have to work together as a collective; by moving past the “imagined community” and developing strategies based around the “place-identity” for a more localized approach that does not compromise the identity or the sustainability of the urban ecology.